A Neat Git(hub) Workflow for Pull Requests

This post is for a friend of mine, so that he can stop bugging me.

I love git and I love Github. Contributing to projects on Github is cool but not always easy if you don’t know where to start. This post presents a neat workflow for handling your Github forks and pull requests.

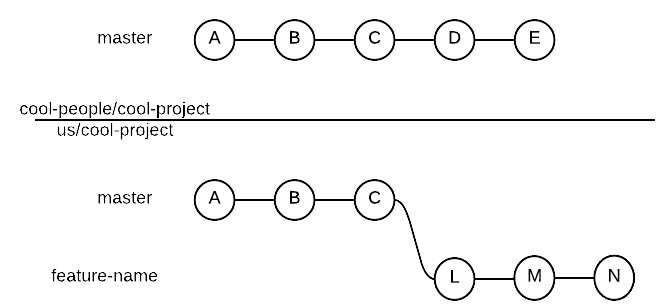

Assume we forked the cool-people/cool-project repository and that we cloned it on our machine.

Adding the Upstream Remote

First, let’s add a remote for the original repository and call it upstream (you can pick

your preferred name here), it will come handy later.

git remote add upstream <address of cool-people/cool-project>

Creating a New Local Branch

As we are git people we don’t develop our new feature/fix/whatever in the master branch, right?

Let’s create a branch for our new feature and move to it

(name feature can be changed to your favourite name, choose a meaningful name):

git branch feature

git checkout feature

Or directly:

git checkout -b feature

And here we go, writing amazing code.

Handling Conflicts with Upstream’s Master

Once we are done coding and we committed our changes we would like to send our feature back to

cool-people/cool-project’s master branch. But what if cool-people/cool-project has gone ahead?

We might be in the following situation:

And even worse, imagine commits D and E are in conflict with our L, M and N commits.

That is, our feature now conflicts

with cool-people/cool-project’s master branch and we need to fix this before sending our pull request.

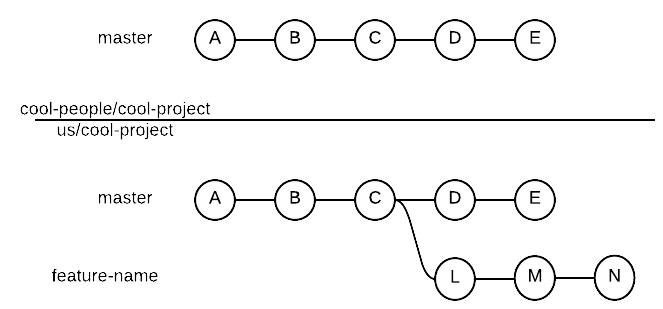

Let’s first update our master branch:

git checkout master

git fetch upstream

git merge upstream/master

We can update our remote master branch as well:

git push origin master

Now that our master branch is up-to-date with cool-people/cool-project’s master we are in the following state:

But we haven’t solved our conflict problem yet.

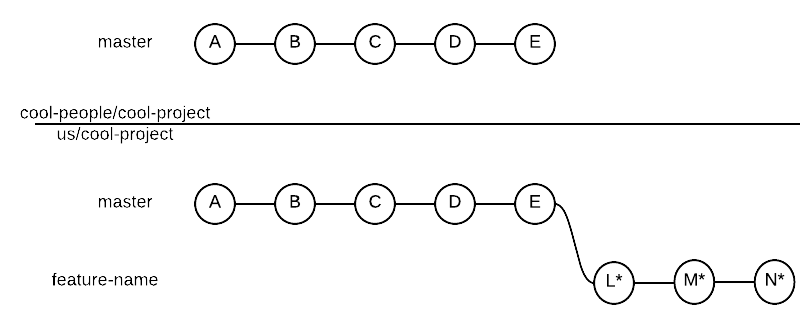

To import master changes into our feature branch and resolve conflicts we use git rebase:

git checkout feature

git rebase master

If there are conflicts bewteen our commits and master’s, the above command will tell us.

If that is the case it’s our duty to resolve conflits and git add the files we modified.

Once we resolved all conflicts we can continue rebasing with:

git rebase --continue

Rebase does the following:

- Imports all missing commits from

masterinto thefeaturebranch - Creates a new commit (L*, M* and N*) for each commit previously in the

featurebranch - Moves new commits (L*, M* and N*) after the last commit imported from

master

To better understand this, here’s our history state after rebasing:

Push our Changes

To update our remote feature branch after rebasing we can use the usual git push.

If we have never pushed the branch, we can simply do:

git push origin feature

If we have already pushed it we must force a push, as rebase created non-fast-forward changes (and git by default prevents us from pushig non-fast-forward changes):

git push origin feature -f

We can now go to Github and press the “Compare & pull request” button for the feature branch.

This will allow us to finalize our pull request.

Why Rebase?

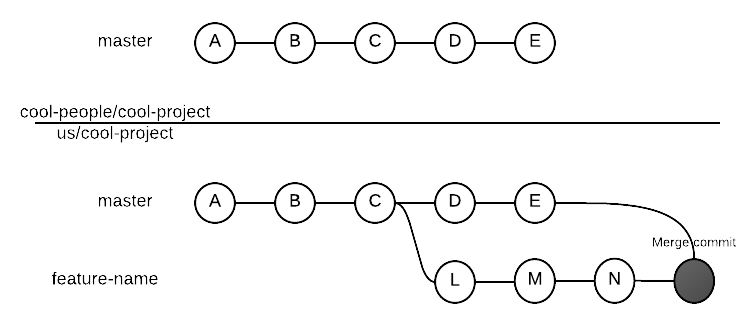

You might now be asking: why did we use git rebase rather than git merge?

The answer to this questions can be found in what merge does to the history, when compared with rebase.

Here’s what would have happened to our history if we used merge instead of rebase:

By sending a pull request from our feature branch we are asking cool-people/cool-project to add

to their history our commits. Do you think cool-people would ever be interested in adding to their

history a merge commit between your branch and their own stuff? I don’t think so.

Rebase, more that merge, can help you send pull requests with a clean history, avoiding commits that add no meaningful information to the history.

Why Not Rebase?

WITH GREAT POWER THERE MUST ALSO COME – GREAT RESPONSIBILITY!

Rebase is a powerfull tool and helps you avoiding dirt in the history. However, as we’ve seen, rebase involves creating non-fast-forward changes. Pushing such changes is never a good idea if your branch is used by other people: rebased commits are new commits, users working on old ones will have a very unpleasent surprise if you rebase their remote branch!

You can safely use rebase when your feature branch is local (i.e. you haven’t pushed it yet), or when you

are sure to be the only person working on that branch (which is often the case for pull requests).